When John Lennon released “Give Peace a Chance” on the fourth of July 1969, he gave

to the world not only an anthem in protest of the conflict in Vietnam, but what is still

perhaps the most famous peace song of all time. Much of the lyrics during the verses is

hard to make out – it was recorded, after all, in a bustling hotel room in Montreal,

Quebec, during Lennon and Ono’s “Bed-in” honeymoon. But that does nothing to take

away from the sheer power and simplicity of the famous chorus: ‘All we are saying is

give peace a chance.’

In a world rife with military aggression, music seems to have the potential to contribute

to peace and conflict resolution. An extensive 2010 study exploring the attitudes and

beliefs of musician-activists regarding the role of music in community engagement,

found that ‘current approaches to conflict resolution will benefit from an increased

awareness of how music can be used to foster healthy relations between individuals and

within a community.’

Yet the question regarding the relation between music and peace is by no means a simple

one: it is fraught with difficulty. Certainly, as we know from the songs of Lennon, Bob

Dylan and many others, music is able to speak the language of peace. What allows music

to do this is its uncanny ability to communicate directly, immediately as it were with our

deepest longings, with the self at its most primordial and vulnerable. To appreciate the

relationship, the internal, even essential connection between music and social harmony

we need to understand something about music and the self more basically. If music has

the capacity to foster peace, to help overcome, or heal the pain associated with conflict, it

is because music is dialogical: a dialogue – an improvised dialogue within, among and

between selves as this radical openness.

But here is also where matters can become complicated, because the primordial self is

also characterized by aggressive strains, and music is well suited to express and even

perhaps sharpen such instinctual drives. If music can unite, it can also divide. There is a

diffuse and general tendency to suppose that music is especially adapted to peace and

non-violence. But such an assumption is simply unsustainable. Can we forget the scene in

Apocalypse Now, when the Americans led by Robert Duvall’s character descend on the

Vietnamese village to the strains of Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyrie”? And certainly,

there is nothing fictional about this idea: US Army tanks in Iraq were equipped to play

compact discs for soldiers as they go into battle. As one put it, ‘It’s the ultimate rush’

when you have a good song playing in the background during a raid. Kosovo Albanians

employed music videos to get their message across, creating national identity while

preparing for war. In the Balkans, music was explicitly used to intimidate: ‘the Cetniks

would set up loudspeakers and play ‘turbofolk’ at a high volume, sometimes for extended

periods of time, before, during, or after shelling.’

Music speaks to the whole of man; and if the past is any guide, then we must admit that

man is a warring creature, as much as he is a creature that longs for peace and

reconciliation. It has been said that war is a drug – and indeed the same may be said for

music, and certain forms of musical experience. Music, it is well known, has an

intoxicating power. The rush of battle and the rush provided by certain kinds of music

can be and are used to enhance or augment one another. This capacity that music

possesses to effectively alter a person’s state of consciousness, to induce a kind of trance-

like state, is a phenomenon that needs to be more fully grasped.

It is often said, following Alfred North Whitehead, that all philosophy is a footnote to

Plato. When it comes to musical education this is certainly true. Plato famously stresses

the importance of music for the auxiliary class, that part of society which is charged with

protection and exemplifies the virtues of the warrior – namely courage, camaraderie, etc.

At the same time there were certain musical scales that Plato would not allow in his ideal

state because they were harmful, as far as their influence on the auxiliaries was

concerned. Too much and the wrong kind of music could ‘tear out the sinews of the soul’

and leave the warrior weak and effeminate. Plato does not want to safeguard music

because it will help generate peace but because it can instill the appropriate virtues in the

military class, whose job is ultimately fighting, defending, and protecting those who

cannot protect themselves.

We might also mention in passing the importance of music in the life of the so-called

prophetic guilds or bands during the earliest period of Hebrew prophecy. These bands of

prophets would roam the countryside and with timbrel, lyre, and flute, they would work

themselves up into a state of ecstasy. At that stage, when prophecy was a collective

endeavor, we might also add that there was also an interest in energizing a movement

towards political independence (from the Philistines). Music here is related to divinely

inspired, prophetic ecstasy. Its aim is not peace, either politically or spiritually, but

renewal, political rebirth perhaps. It is undoubtedly an expression of hope, confidence in

the power of and potential for transformation through religious revival.

What must we conclude from the above? Surely no other conclusion is possible than that

music is not inherently, or essentially peaceful: ‘groups or individuals who want to create

or maintain conflicts have often made good use of music to further their agenda.’

Music is a dialogical event, a kind of improvised conversation between selves that have

agreed to participate in a shared language, a shared world of meaning. Harmony is not

simply an aesthetic conjunction of tones, it is not only created – harmony is creative: it

does things, it is performative, it makes things happen; and it only comes into being

where someone is willing to engage in a dialogue, either with other selves that are

physically present, or with a tradition, a living language that is shared and understood by

some kind of community. Which is just to say that music is a social enterprise through

and through, which is not to deny that music is also intensely personal, the song that one

sings to God in one’s infinite solitude. Music is both, like man himself. Man is an “I” –

but the “I” is only possible in and through the “We”.

Music does not necessarily contribute to peace or the suspension of our aggressive drives.

But as the folk singer, Pete Seeger (played by Edward Norton) says in the new movie

about the early Bob Dylan, A Complete Unknown (2024), ‘A good song can only do

good.’ There is no less a need today for songs that can do good, that can lead to conflict

transformation, and foster peace and justice – precisely because music can just as easily

be used for very different or even opposite ends.

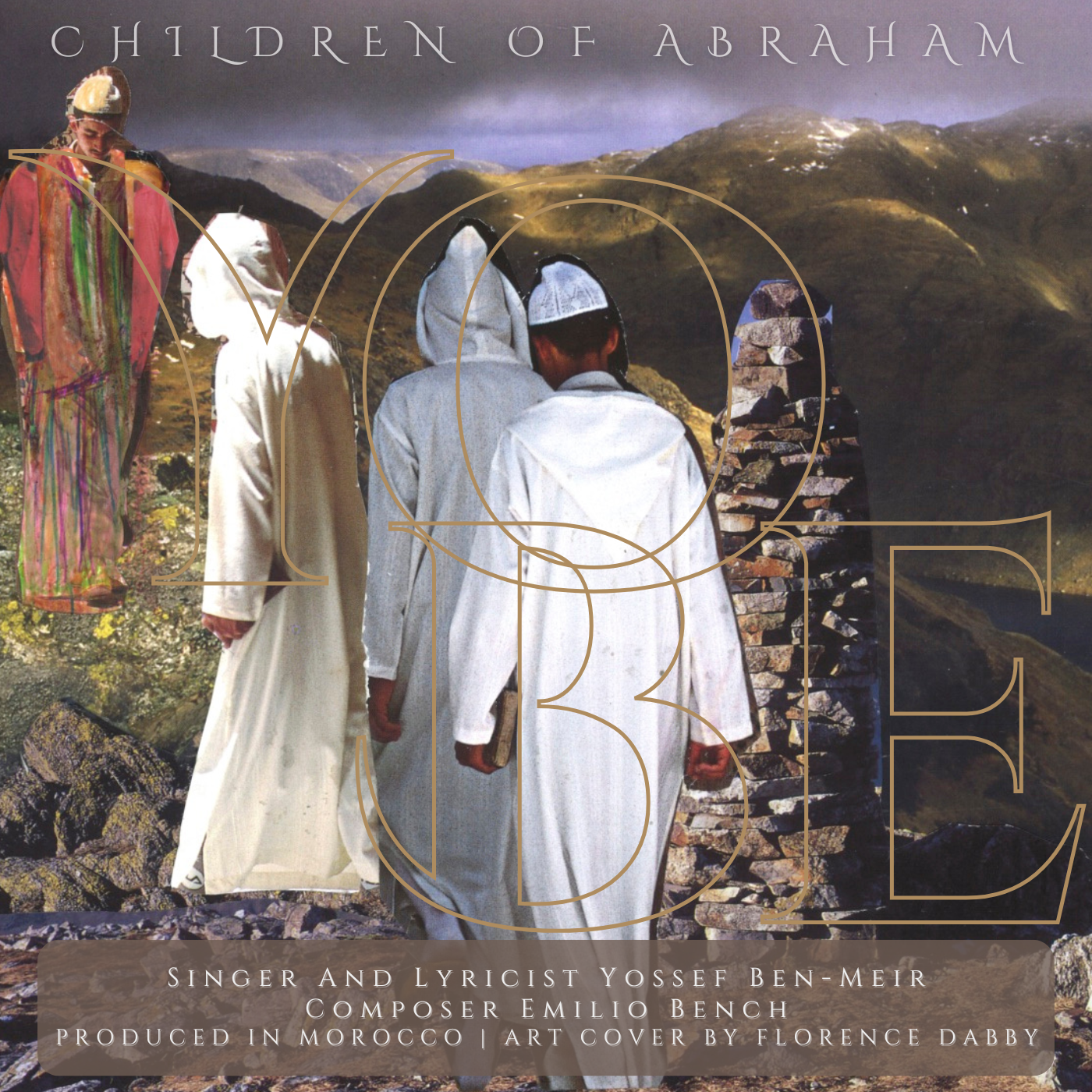

This brings me to the new song, “Children of Abraham,” by YoBe (Yossef Ben-Meir and

Emilio Bench), which is part of a long tradition of peace songs (on Spotify and Youtube).

The lyrics of the energetic chorus, sung in Arabic, are ‘Salam alaikum’ – which translates

to ‘Peace be upon you.’ The title of the song is a reminder that that Judaism, Christianity

and Islam do not simply agree in worshipping one God, but that that they worship the

same one God: that is, the God that revealed Himself to Abraham as recorded in the Book

of Genesis. Jews, Christians and Muslims are indeed all children of Abraham. Sometimes

we need to be reminded of what all already know – that we are all brothers, and sisters –

and, to quote Matthew 25:40: “That which you do to the least of these you do to me.”

If it is true that a good song can only do good, then YoBe’s “Children of Abraham” can

only do good – and that is the most one can ask of any song.

Sam Ben-Meir is an assistant adjunct professor of philosophy at City University of New York, College of Technology.